The Cheviot the Stag and the Black Black Oil - BBC

The following is an excerpt from the essay written by Dr Jonathan Murray for the booklet included with The Cheviot the Stag and the Black Black Oil Blu-ray. The booklet also includes an essay by Dr Sìm Innes on the use of Gaelic in the play and translations of the Gaelic songs.

The Cheviot, the Stag and the Black, Black Oil

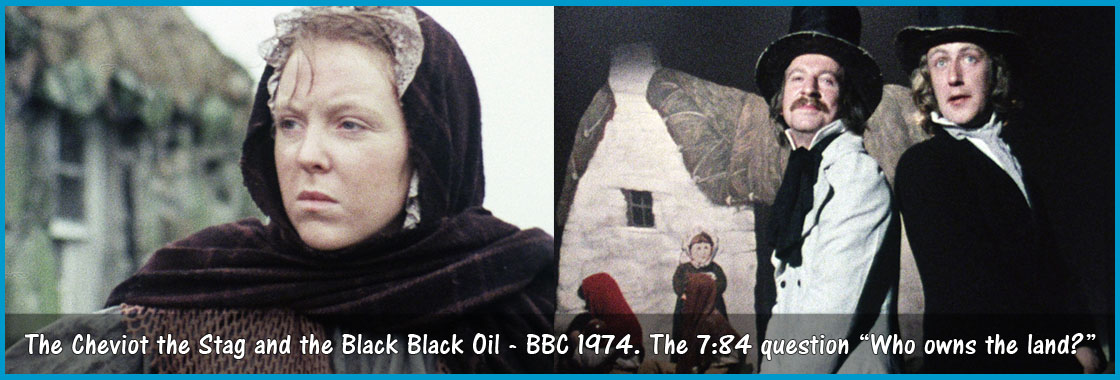

The question “Who owns the land?” lies at the heart of writer John McGrath’s classic 1973 play The Cheviot, the Stag and the Black, Black Oil. But to appreciate the remarkable sense of political power and urgency with which this work poses that query, we might also ask ourselves who or what owns the play. After all, the cast of director John Mackenzie’s 1974 BBC TV adaptation includes both professional actors and hourly-paid oil riggers; historical reconstruction rubs shoulders with contemporary documentary interview; human tragedy and brutality alternates with music hall vitality and hilarity; a performance that talks about the past also has a lot to say about the present. At the levels of content and form alike, The Cheviot has a strong claim to be the most provocative, intelligent and enjoyable screen representation of post-1746 Highland history ever made.

A large part of that achievement stems from the fact that McGrath and Mackenzie’s play-cum-film puts its money where its mouth is from start to finish: The Cheviot argues for the importance of collective ownership and action by turning itself into a collectively authored work of protest and performance. The first thing we see of the source play pre-opening titles, for instance, is local people being played into a one-night-only venue (Dornie Hall) by a cast member bowing beautifully on his fiddle. Once inside, performers and audience encourage each other on in a raucous rendition of Jimmy Copeland’s ‘These Are My Mountains’, printed lyrics held aloft on a white sheet so that none is left out. The words of Copeland’s song propose that the land upon which this particular performance of it takes place belongs to everyone (and thus, to no one person in particular). By going out of their way to involve audience members in the singing, The Cheviot’s formally credited author, cast and director propose the same idea about a text and performance that is at no point exclusively or straightforwardly “their” property. The idea that the choice between individual and communal modes of performance is intensely political in nature then resurfaces at numerous points and in numerous ways throughout the film’s remainder. It seems no accident, for example, that each member of the parade of eighteenth-to-twentieth-century grotesques who proselytise on behalf of vested interests past and present do so in not-so-splendid oratorical isolation. A landowner-friendly Presbyterian Minister won’t even permit the semi-silent sooking of Pan Drops while he thunders against “flagrant transgression of authority” from his pulpit’s commanding heights; a drag Queen Victoria drops by briefly to bestow a few regal words upon his/her grateful subjects; the third Duke of Sutherland falls flat on his face trying to recruit his exploited tenants to fight in the Crimean War.

The pronounced historical and political importance that The Cheviot attaches to ideas of cooperation and collectivism exerts a decisive influence on the painstakingly precise approach that the work takes towards researching and recounting Highland history between the 1740s and 1970s. To be more specific, we could say that this play-cum-film is at once hugely attracted to and profoundly alienated by the idea of ‘the view from above’. Taking the alienated response first, John Mackenzie’s film of The Cheviot repeatedly associates literally elevated perspectives (i.e., aerial shots) with the potentially or actually destructive exercising of physical, economic and/or technological muscle. The work’s bravura opening image shows the landmass of Scotland viewed from the space-bound perspective of an American astronaut who is, perhaps, a relation of the all-powerful US oilmen descending on that country in droves: as he flies back to Texas (the spaceman is heard addressing NASA’s Houston HQ), they fly out. Similarly, the visual rhyme the film constructs between shots of Eilean Donan and Dunrobin Castles and those of North Sea oil rigs works to suggest that autocracy has not died, but merely moved its preferred seat of power, as the centuries have progressed. More importantly yet, however, The Cheviot is implacably hostile towards instruments and/or interpretations of historical change that are fashioned by individuals and interest groups whose economic privilege and power blinds them to the human suffering caused by inequitable forms of wholesale socioeconomic change. The work is contemptuous, for example, of the successive generations of self-proclaimed men of Progress and Reason spawned by notorious historical figures like the early-nineteenth-century Edinburgh lawyers Patrick Sellar and James Loch. Viewers see Sellar and Loch inaugurate the first fatal wave of Clearances in early-nineteenth-century Sutherland by proclaiming the non-existence virtues of platitudes such as “High Industry,” “wealth, comfort… virtue and happiness.”